Overview

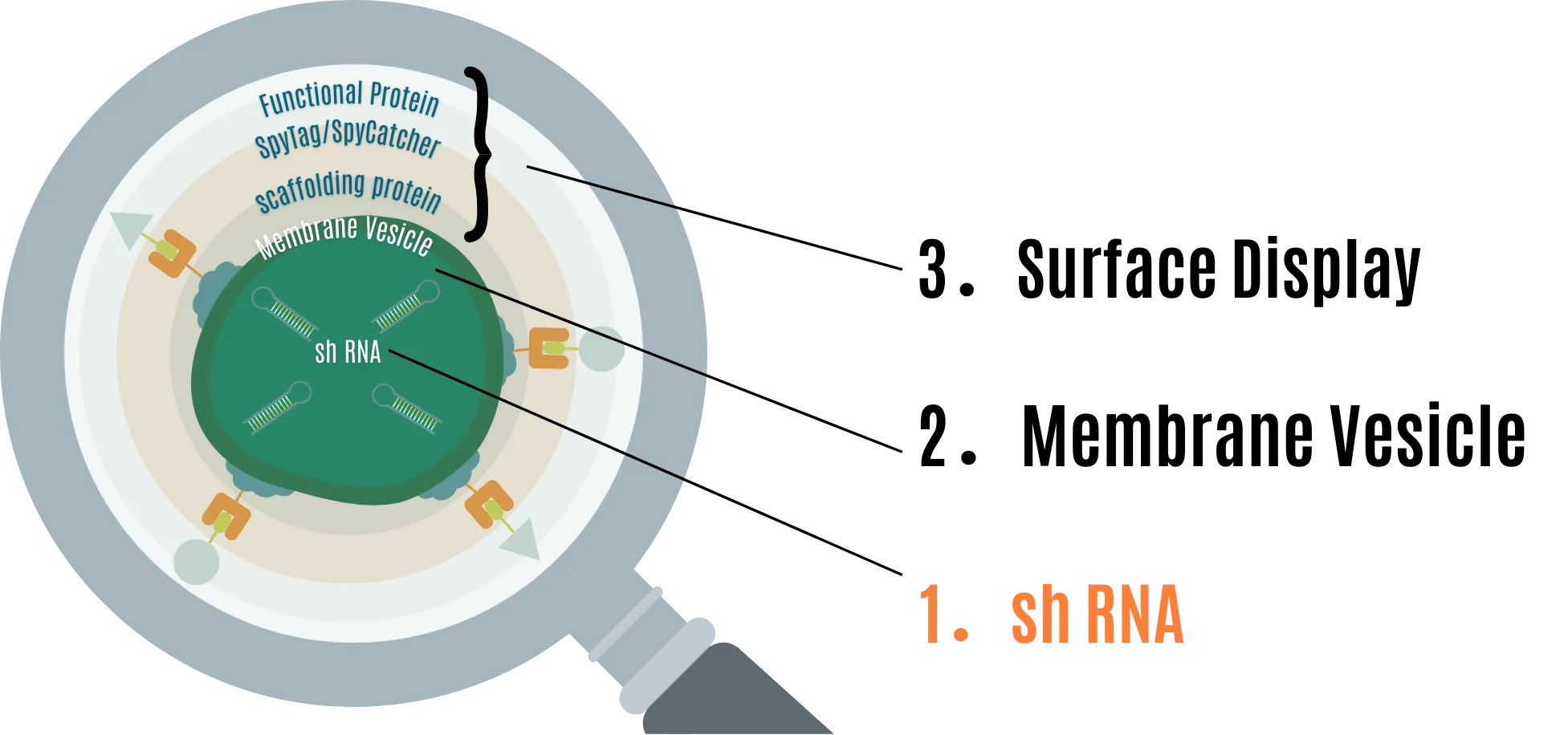

We approached this project with the aim of constructing a system that prevents RNA pesticides from degrading in the environment and extends their effective period as pesticides, focusing on the low persistence of RNA pesticides. Our MOVE is primarily designed from:

- shRNA for RNAi

- Extracellular vesicles (MV) to protect shRNA

- Surface display to provide extensibility to MV

With this design, RNA pesticides are not only protected from functional degradation by the environment but can also have extensibility through several functional proteins.

1. shRNA for RNAi

RNA interference is a natural process that targets mRNA, degrading it through multiple steps to inhibit translation. RNAi is conserved in almost all eukaryotes, including fungi, plants, and animals [1] .

There are small molecules that induce RNAi other than shRNA, such as dsRNA, pre-miRNA, and siRNA. This time, we use shRNA, which has a hairpin loop structure of about 30 bases, focusing on the expectation of stable production from the vector. [2] .

The mechanism of RNAi action triggered in eukaryotes using shRNA as the active agent is shown in Figure 1 [3] . After transcription, shRNA is sent to the cytoplasm where it is processed into siRNA double strands by a protein called Dicer. The generated siRNA duplex is incorporated into a multi-protein complex called the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), and the sense strand is removed. The remaining guide (antisense) strand performs mRNA silencing. The guide strand in RISC binds the complex to complementary mRNA transcripts via Watson-Crick base pairing, and enzymes called Argonaute proteins (specifically Ago2 in the case of siRNA) degrade the target mRNA [4] .

2. Membrane Vesicle (MV) to protect shRNA

MVs are spherical structures formed by lipid bilayers produced by gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. They are generally 20nm to 500nm in size [5] [6] . These are used as carriers of substances, employed in communication signals between bacteria, genetic information, and even in signal exchange with eukaryotic cells that become hosts [7] . We considered MVs suitable as a means to protect shRNA because they are derived from biological membranes, thus having low environmental impact, and can isolate encapsulated substances [7] [8] .

In gram-negative bacteria, MVs are thought to be mainly produced by a process called Blebbing, where the outer membrane bulges, and the causes vary depending on the species [9] .

-

Loss of outer membrane-inner membrane binding

MV formation is induced by the loss of lipoproteins involved in outer membrane binding or peptidoglycan (PG) that bridges the outer and inner membranes.

-

Curvature of the outer membrane

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) existing on the outer surface of the outer membrane is negatively charged, and the repulsive force they generate causes the membrane to curve, inducing MV formation.

-

Various stresses

MV formation is induced when cell wall components such as PG or misfolded proteins accumulate in the space between the outer and inner membranes, increasing internal pressure. MV is also formed when the membrane bulges due to various inductions such as antibiotics, oxidative stress, or heat stress.

In this project, we designed MV formation by Blebbing using E. coli, a gram-negative bacterium.

Although MVs are released as a general activity of bacteria, their release amount is small [10] and it is easy to imagine that it is not enough for industrial use. Therefore, we introduced PIA-MVP (Polymer Intracellular Accumulation-triggered system for Membrane Vesicle Production) to E. coli to give it a higher MV production capacity.

PIA-MVP is a mechanism developed by Professor Taguchi and Assistant Professor Koh at Kobe University, which can greatly increase MV production by internal pressure caused by poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) produced and stored in E. coli [11] . By introducing the phbCAB synthesis gene operon derived from the natural PHB-producing bacterium Ralstonia eutropha, PHB is produced in the following flow:

This pathway increases PHB production in a glucose concentration-dependent manner in the medium. Therefore, we can control MV production with high flexibility by adjusting the glucose concentration in the medium.

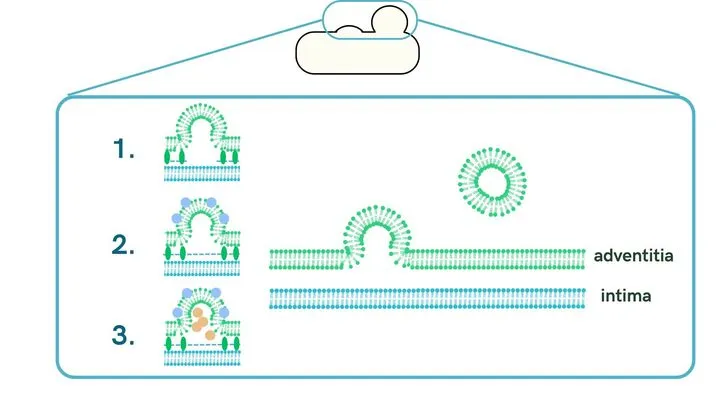

Gram-negative bacteria have inner and outer membranes, and in normal MV release by Blebbing, single-layer MVs (s-MVs) composed only of the outer membrane are mainly produced. On the other hand, the MV generation method by PIA-MVP can generate multi-layer MVs (m-MVs) that have both outer and inner membranes. This allows efficient encapsulation of substances in the cytoplasm [12] . We proposed to incorporate shRNA produced in E. coli into MVs using this technology.

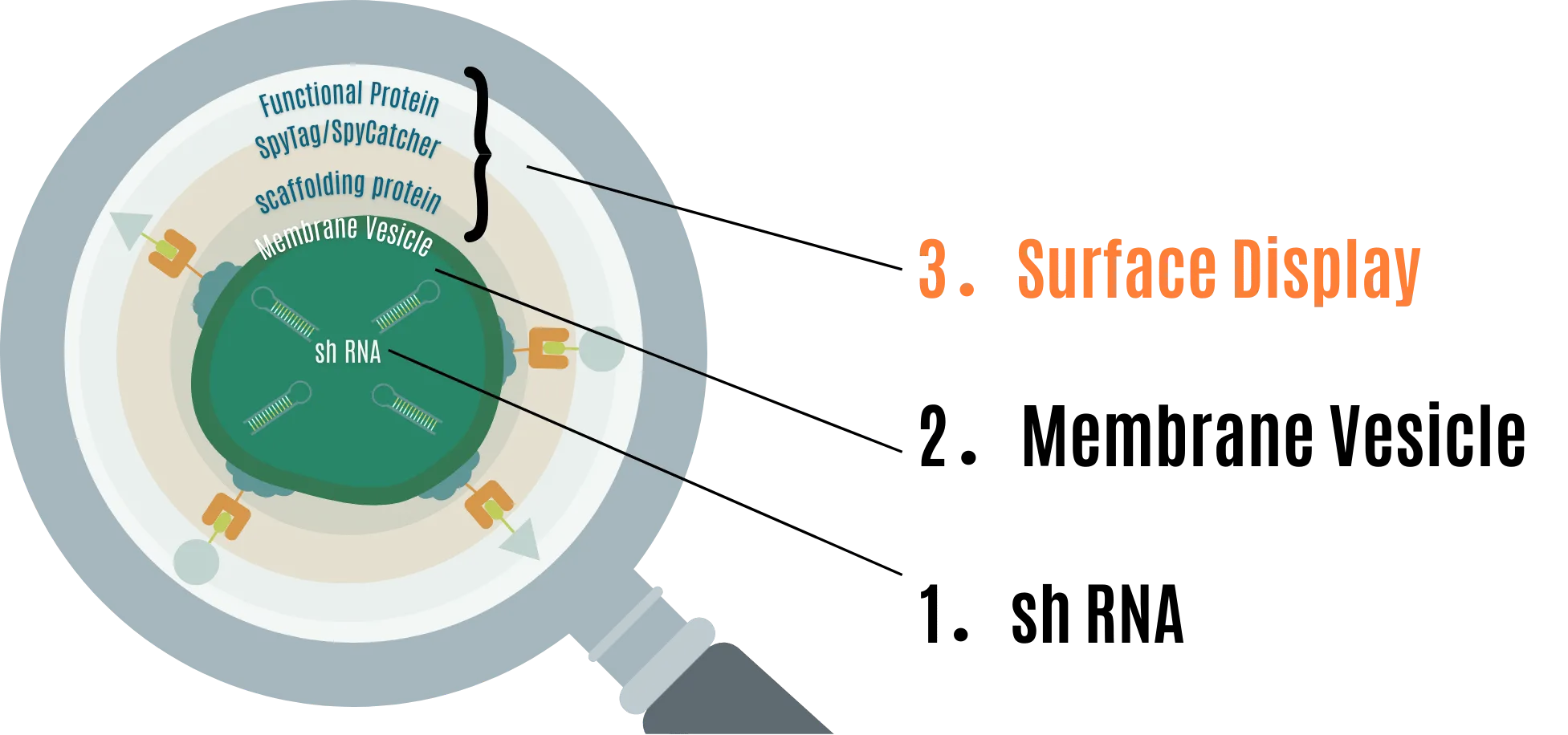

3. Surface display to provide extensibility to MV

To use RNA-encapsulated MVs as pesticides, it was necessary to provide MVs with stable uptake efficiency into target pathogens and a certain level of persistence required for pesticides. To address this issue, we focused on the ability of E. coli producing MVs to surface display specific proteins [13] .

Surface display is a technology that can change the surface structure of cells or give them catalytic functions by fusing various functional proteins with scaffold proteins existing on the cell surface [14] .

Considering that MVs are derived from E. coli membranes, surface display can also be performed on MVs [15] . The function of MVs can be enhanced by surface displaying proteins that aid in uptake by pathogens or increase persistence as pesticides.

As an example, we designed the protein presentation for a fungi. The scaffold proteins used for surface display this time are LPP-OmpA [16] and ice nucleation protein (INP) [17] used in E. coli. As functional proteins, we are using chitinase C [18] , GH19 chitinase [19] , and glucanase [20] , which degrade chitin and β-glucan used as cell walls by pathogens (fungi), as proteins to aid in uptake by pathogens. We also used Mgfp5 [21] , an adhesion protein from mussels, to increase persistence on leaves and such.

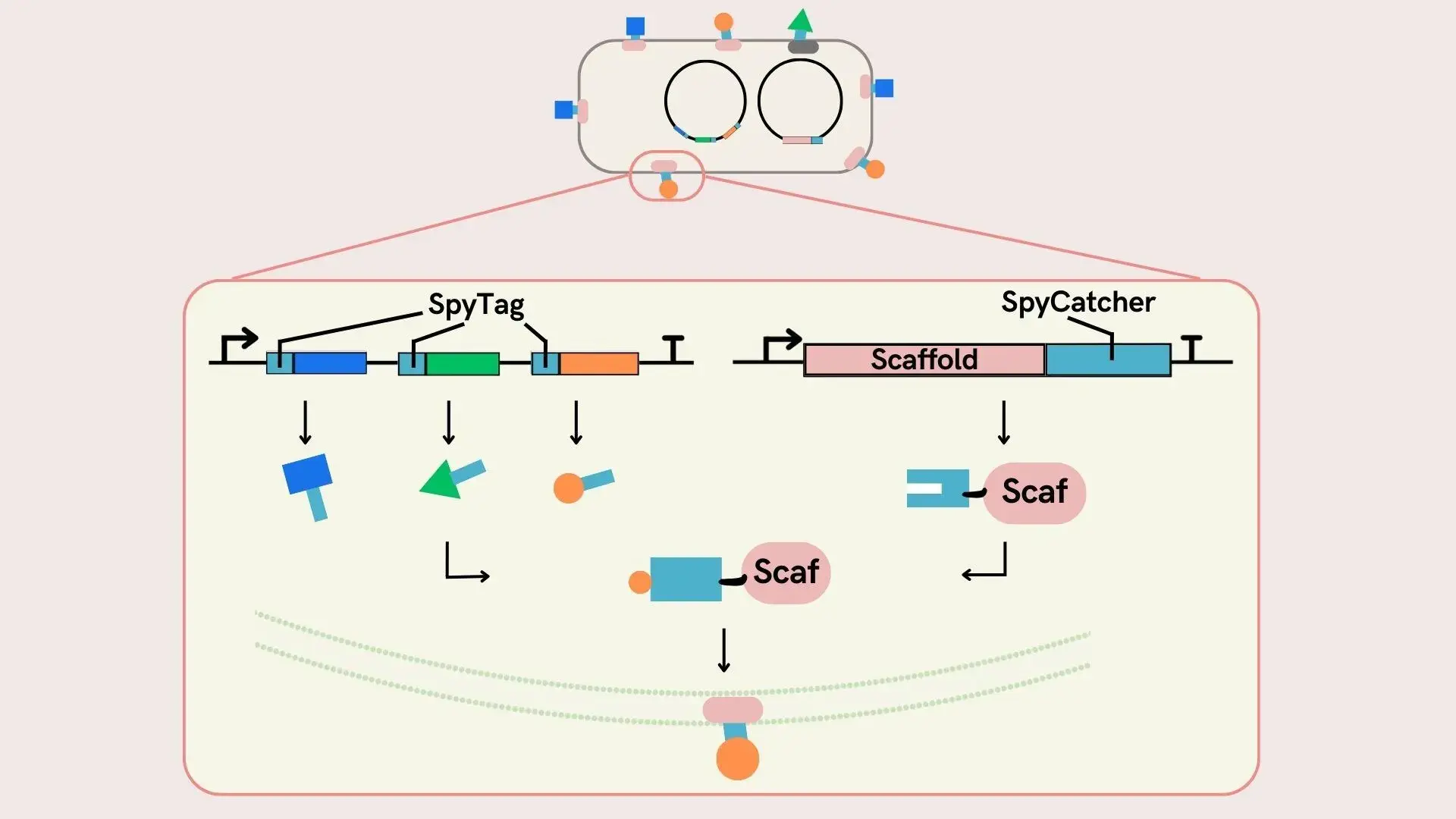

Surface Display using SpyCatcher-SpyTag system

We decided to use the SpyCatcher-SpyTag system to display multiple proteins on the same membrane surface. The SpyCatcher-SpyTag system naturally forms isopeptide bonds between SpyTag, a short peptide, and SpyCatcher, a small protein [22] . Here, we are simultaneously expressing a protein with SpyCatcher fused to the terminus of the ice nucleation protein INP-NC, which serves as a scaffold for E. coli to surface display proteins, and a protein with SpyTag fused to the terminus of the surface display protein. As a result a fusion protein INP-NC-SpyCatcher-SpyTag-surface display protein in the cell, which is transported to the cell surface and displayed on the surface. Normally, functional proteins are prepared in multiple types for each product, so we ensured modularity by separating scaffold proteins and functional proteins. In other words, when changing the protein to be surface displayed, there is no need to change the expression of SpyCatcher, which is only the expression of the functional protein with SpyTag needs to be changed.

With this system, surface displayed proteins presented on the E. coli surface are added to RNA-encapsulated MVs, contributing to enhancing the effect of MOVE as an RNA pesticide.

References

[1] Gutbrod MJ, Martienssen RA. Conserved chromosomal functions of RNA interference. Nat Rev Genet, 311-331(2020).

[2] Barøy T, Sørensen K, Lindeberg M, M. et al. shRNA Expression Constructs Designed Directly from siRNA Oligonucleotide Sequences. Mol Biotechnol 45 , 116–120 (2010).

[3] Saito-Tarashima N. Chemical Approaches for RNAi Drug Development. Yakugaku Zasshi. 1259-1268(2020).

[4] Singh, S., Narang, A.S. & Mahato, R.I. Subcellular Fate and Off-Target Effects of siRNA, shRNA, and miRNA. Pharm Res 28 , 2996–3015 (2011).

[5] Toyofuku M, Roschitzki B, Riedel K, Eberl L. Identification of proteins associated with the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm extracellular matrix. J Proteome Res. 4906-15(2012).

[6] Min Li, Han Zhou, Chen Yang, Yi Wu, Xuechang Zhou, Hang Liu, Yucai Wang,Bacterial outer membrane vesicles as a platform for biomedical applications: An update,Journal of Controlled Release,Volume 323,253-268(2020).

[7] Xiao M, Li G, Yang H. Microbe-host interactions: Structure and functions of Gram-negative bacterial membrane vesicles. Frontiers in Microbiology, 14, 1225513(2023).

[8] Morales-Jiménez, M., Palacio, D. A., Palencia, M., Meléndrez, M. F., & Rivas, B. L. Bio-Based Polymeric Membranes: Development and Environmental Applications. Membranes, 13(7)(2023).

[9] Obana N, Kurosawa S, Toyohuku M, Nomura N. Biogenesis and Functions of Membrane Vesicles Actively Produced by Microbes.Kagakuto Seibutsu. 54 (11), 812-819(2016).

[10] Reimer SL, Beniac DR, Hiebert SL, Booth TF, Chong PM, Westmacott GR, Zhanel GG and Bay DC . Comparative Analysis of Outer Membrane Vesicle Isolation Methods With an Escherichia coli tolA Mutant Reveals a Hypervesiculating Phenotype With Outer-Inner Membrane Vesicle Content. Front. Microbiol. 12:628801(2021).

[11] Koh, S., Sato, M., Yamashina, K., Usukura, Y., Toyofuku, M., Nomura, N., & Taguchi, S. Controllable secretion of multilayer vesicles driven by microbial polymer accumulation. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1-9(2022).

[12] Koh S, Noda S, Taguchi S. Population Dynamics in the Biogenesis of Single-/Multi-Layered Membrane Vesicles Revealed by Encapsulated GFP-Monitoring Analysis. Appl. Microbiol. 3(3), 1027-1036(2023).

[13] Hori K, Interfacial Microbiology and Engineering: From BiofilmEngineering to Cell Surface Engineering. Kagaku to Seibutsu 59(8): 393-400 (2021).

[14] Francisco, J., Stathopoulos, C., Warren, R. et al. Specific Adhesion and Hydrolysis of Cellulose by Intact Escherichia coli Expressing Surface Anchored Cellulase or Cellulose Binding Domains. Nat Biotechnol 11 , 491–495 (1993).

[15] van den Berg van Saparoea HB, Houben D, de Jonge MI, Jong WSP, Luirink J. Display of Recombinant Proteins on Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles by Using Protein Ligation. Appl Environ Microbiol84:e02567-17(2018).

[16] Nicchi, S., Giuliani, M., Giusti, F. et al. Decorating the surface of Escherichia coli with bacterial lipoproteins: a comparative analysis of different display systems. Microb Cell Fact 20 , 33 (2021).

[17] Jung, HC., Lebeault, JM. & Pan, JG. Surface display of Zymomonas mobilis levansucrase by using the ice-nucleation protein of Pseudomonas syringae. Nat Biotechnol 16 , 576–580 (1998).

[18] Li X, Jin X, Lu X, Chu F, Shen J, Ma Y, Liu M, Zhu J. Construction and characterization of a thermostable whole-cell chitinolytic enzyme using yeast surface display. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 77-85(2014).

[19] Bai L, Kim J, Son KH, Chung CW, Shin DH, Ku BH, Kim DY, Park HY. Novel Bi-Modular GH19 Chitinase with Broad pH Stability from a Fibrolytic Intestinal Symbiont of Eisenia fetida, Cellulosimicrobium funkei HY-13. Biomolecules.21;11(11):1735(2021).

[20] Niu C, Li X, Xu X, Bao M, Li Y, Liu C, Zheng F, Wang J, Li Q. [Research progresses in microbial 1,3-1,4-β-glucanase: protein engineering and industrial applications]. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao. 25;35(7):1234-1246(2019).

[21] Hwang DS, Gim Y, Kang DG, Kim YK, Cha HJ. Recombinant mussel adhesive protein Mgfp-5 as cell adhesion biomaterial. J Biotechnol. 20;127(4):727-35(2007).

[22] Zakeri, B., Fierer, J. O., Celik, E., Chittock, E. C., Moy, V. T., & Howarth, M. Peptide tag forming a rapid covalent bond to a protein, through engineering a bacterial adhesin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(12), E690-E697(2012).